We all know from experience that there seems to be a connection between reward and learning. We see it clearly in children; “Honey, you can watch one more hour of TV tonight if you clean your room.” The child now has an incentive to clean his room.

In fact, you can find this reward system used everywhere even in adults’ world. Many companies have a bonus system to motivate employees to work harder. Prizes and awards are given out on just about any skill that can be measured. In short, rewards seem to have a great part in motivating and teaching people.

Why rewards work? Why a person’s behaviour changes when his actions are rewarded? How does this work inside the brain? And above all, how can you use rewards when training people to reinforce learning?

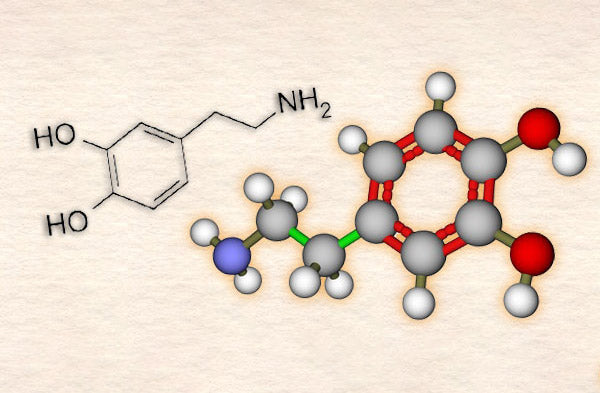

Let’s start with reward seeking behaviour of humans. In 1959 it was discovered that a neurotransmitter called dopamine (DA) is strongly involved in control of movements. Since then studies have been conducted that have identified the critical role of dopamine in the brain reward system (Arias-Carrion and Poppel 2007).

Interestingly, research also shows that dopamine deficiencies can lead to a number of serious diseases such as Parkinson, schizophrenia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

On the other side of the scale, dopamine is also central to drug abuse and addiction.

Some have also associated dopamine with our cognitive development and how we managed to become intelligent as we evolved (Previc 1999).

With so much significance, let’s see how dopamine can relate to learning and how we can take advantage of what it offers.

How Does Dopamine Affect Learning

How do we come to know how to satisfy our thirst or hunger or other bodily needs? Are we programmed from birth to do this? Why do we follow our parents when we are young?

It turns out that we learn these behaviours. Initially we may start with random moves but our actions are selectively reinforced by the environment. The environment teaches us to learn how to satisfy a particular need. Say, you are thirsty. Your mother might give you some water. This leads to stimuli in the DA system that reinforces behaviour that says, “seek mother to get water”. Equally, if you found water by accident in the environment (such as when you lost your mother but were still thirsty), you are likely to go back to the place you found water to take care of your thirst. These behaviours lead to an association between the stimulus and the reward. All of this is managed by the DA system.

Each time you do a specific behaviour, the association is reinforced until it becomes a habit. And here is the interesting point. The association lasts even if the reward is removed. In fact, this association may remain until, through experience, it is devalued.

This is interesting because it makes giving rewards worthy of the effort. If the reward had a short term effect, we would have to constantly learn everything over and over again. Besides, it would have also meant that you would be less inclined to reward others if they know that the reward’s effect will be gone in no time.

Fortunately, we don’t have that problem.

How Does Dopamine Affect Reward-Seeking Behaviour

Rewards are liked, wanted and pursued because they make a person’s life better. The hungrier you are, the more likely you are to go through a lot of effort to find food.

Research on animal behaviour has led to a number of theories on how this process works in practice. One interesting model is reinforcement-learning (Montague et al. 2004). This model has been compared with the DA system and is found that they support each other.

Here is how this model works. For each action, the brain estimates and stores a value based on the amount of reward it receives for doing that action. The animal then uses these stored values to predict the likely reward or punishment for any given action. Once an action is carried out, the actual reward gained is then compared with the prediction. The difference is the “reward prediction error” which can form future behaviour.

This “reward prediction error” is recorded by the DA system and thus forms an essential part of reinforcement-learning behaviours.

To see how the DA works in practice, researches have examined the DA system and its firing patterns in primates (Hollerman and Schultz 1998) and they have found some interesting results.

Monkeys were trained to expect a set amount of sweet juice using classical conditioning. The researchers then examined the firing of the monkeys’ neurons. Normally, the DA neurons have a set pattern of firing. Every time the juice was made available as a reward for an action, there was a burst of firing neurons on top of the normal pattern.

So far so good.

As this was repeated, the monkey started to learn and predict the reward. After a set period, giving sweet juice no longer led to firing of neurons; the reward was just as expected!

The researchers showed that the specific firing patterns of DA neurons could directly indicate if a reward was “as expected”, “better than expected” or “worse than expected”.

How to Apply Reinforcement-Learning to Training

What does this mean for training? If you constantly praise the delegates in a way that becomes expected, you stop reinforcing behaviour. On the other hand, if you stop giving rewards all together, the firing rate goes back to zero (or basic pattern) and the reinforcement value is lost.

Hence, to reinforce learning and to provide a direction based on actions taken, look for ways to surprise people with rewards.

If a reward is given over and over again and eventually is taken for granted, then it can lose its value in shaping someone’s behaviour.

You may need to incrementally increase the value of the reward or manipulate the timing of it so people cannot guess when to expect it. You can then use their reward seeking tendency, as implemented by the DA system to guide them towards a direction of your choice by constantly surprising them.

Easier said than done, but at least you know what to do now.

References:

Arias-Carrion, O., Poppel, E., (2007) “Dopamine, learning and reward-seeking behaviour”, Acta Neurobiol Exp 2007, 67: 481-488.

Previc, F.H., (1999) “Pleasure and pain. Fundamental of human experience and behavior”, Severin und Siedler, Berlin.

Hollerman, J.R., Schultz, W., (1998) “Dopamine neurons report an error in the temporal prediction of reward during learning”, Nat Neurosci 1: 304-309.

Montagu, P.R., Hyman, S.E., Cohen, J.D., (2004) “Computational roles in dopamine in behavioural control”, Nature, 431: 760-67.

Soft Skills Training Materials

Get downloadable training materials

Online Train the Trainer Course:

Core Skills

Learn How to Become the Best Trainer in Your Field

All Tags

Training Resources for You

Course Design Strategy

Available as paperback and ebook

Free Training Resources

Download a free comprehensive training package including training guidelines, soft skills training activities, assessment forms and useful training resources that you can use to enhance your courses.

Our Comprehensive Guide to Body Language

Train the Trainer Resources

Get Insights - Read Guides and Books - Attend Courses

Training Materials

Get downloadable training materials on: Management Training, Personal Development, Interpersonal Development, Human Resources, and Sales & Marketing

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.